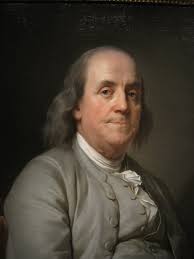

The founders of America were very smart men. They anticipated what would happen to America almost immediately. Benjamin Franklin was asked a question that shows he had a clear understanding of what was directly ahead for us! As Benjamin Franklin departed the Constitutional Convention, he was asked if the framers had created a monarchy or a republic. “A republic,” he famously replied, and then added, “if you can keep it.”

The founders of America were very smart men. They anticipated what would happen to America almost immediately. Benjamin Franklin was asked a question that shows he had a clear understanding of what was directly ahead for us! As Benjamin Franklin departed the Constitutional Convention, he was asked if the framers had created a monarchy or a republic. “A republic,” he famously replied, and then added, “if you can keep it.”

America was set on a course by the framers of the Constitution, that made this nation the greatest nation in the world! But the people who tried and failed to stop it. Set their minds to make sure their desire for a one world slave nation. Would be realized, no matter how long it took them and their children to assemble it! A nation patterned after the nations of Rome and Babylon has always been their goal. They are now within their reach but they will soon find it to be bittersweet! I will now give you some facts about where we are and how we got here. I have much more than I can put into this small post. But I will give you what it takes to come to the conclusion that we have been mugged!

Did you know?

Thomas Jefferson declared in letters that the decision in Marbury v. Madison and the concept of judicial review were unconstitutional and not actually law. But Marbury V Madison is the foundation on which the coup that we are dealing with today was built on over a period of about 240 years!

Quotes From: John Marshall

Chief Justice John Marshall declared that the Judiciary Act of 1789 – which would have allowed the court to issue the writ at stake – was not constitutional and that Congress could not change the U.S. Constitution with regular legislation; thus, the Act was invalid.

The people made the Constitution, and the people can unmake it. It is the creature of their own will, and lives only by their will.

“A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.” With these words written by Chief Justice Marshall, the Supreme Court for the first time declared unconstitutional a law passed by Congress and signed by the President. Nothing in the Constitution gave the Court this specific power. Marshall, however, believed that the Supreme Court should have a role equal to those of the other two branches of government.

Marbury v. Madison

Marbury v. Madison, legal case in which, on February 24, 1803, the U.S. Supreme Court first declared an act of Congress unconstitutional, thus establishing the doctrine of judicial review. The court’s opinion, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, is considered one of the foundations of U.S. constitutional law.

Marbury and his lawyer, former attorney general Charles Lee, argued that signing and sealing the commission completed the transaction and that delivery, in any event, constituted a mere formality. But formality or not, without the actual piece of parchment, Marbury could not enter into the duties of office. Despite Jefferson’s hostility, the court agreed to hear the case, Marbury v. Madison, in its February 1803 term.

The decision

The chief justice recognized the dilemma that the case posed to the court. If the court issued the writ of mandamus, Jefferson could simply ignore it, because the court had no power to enforce it. If, on the other hand, the court refused to issue the writ, it would appear that the judicial branch of government had backed down before the executive, and that Marshall would not allow. The solution he chose has properly been termed a tour de force. In one stroke, Marshall managed to establish the power of the court as the ultimate arbiter of the Constitution, to chastise the Jefferson administration for its failure to obey the law, and to avoid having the court’s authority challenged by the administration.

Marshall, adopting a style that would mark all his major opinions, reduced the case to a few basic issues. He asked three questions: (1) Did Marbury have the right to the commission? (2) If he did, and his right had been violated, did the law provide him with a remedy? (3) If it did, would the proper remedy be a writ of mandamus from the Supreme Court? The last question, the crucial one, dealt with the jurisdiction of the court, and in normal circumstances it would have been answered first, since a negative response would have obviated the need to decide the other issues. But that would have denied Marshall the opportunity to criticize Jefferson for what the chief justice saw as the president’s flouting of the law.

Following the arguments of Marbury’s counsel on the first two questions, Marshall held that the validity of a commission existed once a president signed it and transmitted it to the secretary of state to affix the seal. Presidential discretion ended there, for the political decision had been made, and the secretary of state had only a ministerial task to perform—delivering the commission. In that the law bound him, like anyone else, to obey. Marshall drew a careful and lengthy distinction between the political acts of the president and the secretary, in which the courts had no business interfering, and the simple administrative execution that, governed by law, the judiciary could review.

Having decided that Marbury had the right to the commission, Marshall next turned to the question of remedy, and once again found in the plaintiff’s favour, holding that “having this legal title to the office, [Marbury] has a consequent right to the commission, a refusal to deliver which is a plain violation of that right, for which the laws of his country afford him a remedy.” After castigating Jefferson and Madison for “sport[ing] away the vested rights of others,” Marshall addressed the crucial third question. Although he could have held that the proper remedy was a writ of mandamus from the Supreme Court—because the law that had granted the court the power of mandamus in original (rather than appellate) jurisdiction, the Judiciary Act of 1789, was still in effect—he instead declared that the court had no power to issue such a writ, because the relevant provision of the act was unconstitutional. Section 13 of the act, he argued, was inconsistent with Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution, which states in part that “the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction” in “all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party,” and that “in all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction.” In thus surrendering the power derived from the 1789 statute (and giving Jefferson a technical victory in the case), Marshall gained for the court a far-more-significant power, that of judicial review.

Learn More!

What they were doing here was making the need to have a Constitutional Convention unnessary. It took from the peoples hands the right to decide how and what changes were made to the foundation of our laws!

Did you know?

Thomas Jefferson declared in letters that the decision in Marbury v. Madison and the concept of judicial review were unconstitutional and not actually law.

Chief Justice John Marshall declared that the Judiciary Act of 1789 – which would have allowed the court to issue the writ at stake – was not constitutional and that Congress could not change the U.S. Constitution with regular legislation; thus, the Act was invalid.

Impact

Marshall’s masterful verdict has been widely hailed. In the face of attacks on the judiciary launched by Jefferson and his followers, Marshall needed to make a strong statement to maintain the status of the Supreme Court as the head of a coequal branch of government. By asserting the power to declare acts of Congress unconstitutional (which the court would not exercise again for more than half a century), Marshall claimed for the court a paramount position as interpreter of the Constitution.

Although Marbury v. Madison set an abiding precedent for the court’s power in that area, it did not end debate over the court’s purview, which has continued for more than two centuries. In fact, it is likely that the issue will never be fully resolved. But the fact remains that the court has claimed and exercised the power of judicial review through most of U.S. history—and, as Judge Learned Hand noted more than a century later, the country is used to it by now. Moreover, the principle fits well with the government’s commitment to checks and balances. Few jurists can argue with Marshall’s statement of principle near the end of his opinion, “that a law repugnant to the constitution is void, and that courts, as well as other departments, are bound by that instrument.”

The Matter Becomes Clear

The chief Justice knew that the Constitution was the law and the court had nothing to say about it. The supreme court or no other court can make law! But we see it every day, because of Marbury V Madison, which isn’t law. Therefore any time it is done, it isn’t legal!

So by the time our nation reached 1803 we were seeing the coup to change our Republic to a Democracy! Today in 2021 we find the coup coming full circle. The are mountains of evidence that not only the last election was fraud filled. But our entire Republic has been hijacked because we are allowing it!

At any point in time we the people could stop it by saying. It doesn’t work and we are disolving it and returning to the Constitution as written! We created the Federal government that we have. All of the power that the federal government had was given to them by us. Not all of the power they are claiming was actually given to them. It has be userped and was never legally theirs!

When Marbury V Madison was made Constitutional the change from a Republic to a Democracy was started. The theives only turn to the Constitution when it helps achieve their goal. From 1803 until this day you have not had a Republic but a Democracy. Any person in the President, Congress or supreme court understands that and feels free to take an oath to a Constitution they have no intention of “preserving or protecting”!